Invisible Hand

2021

Installation

h314 × w170 × d170 cm

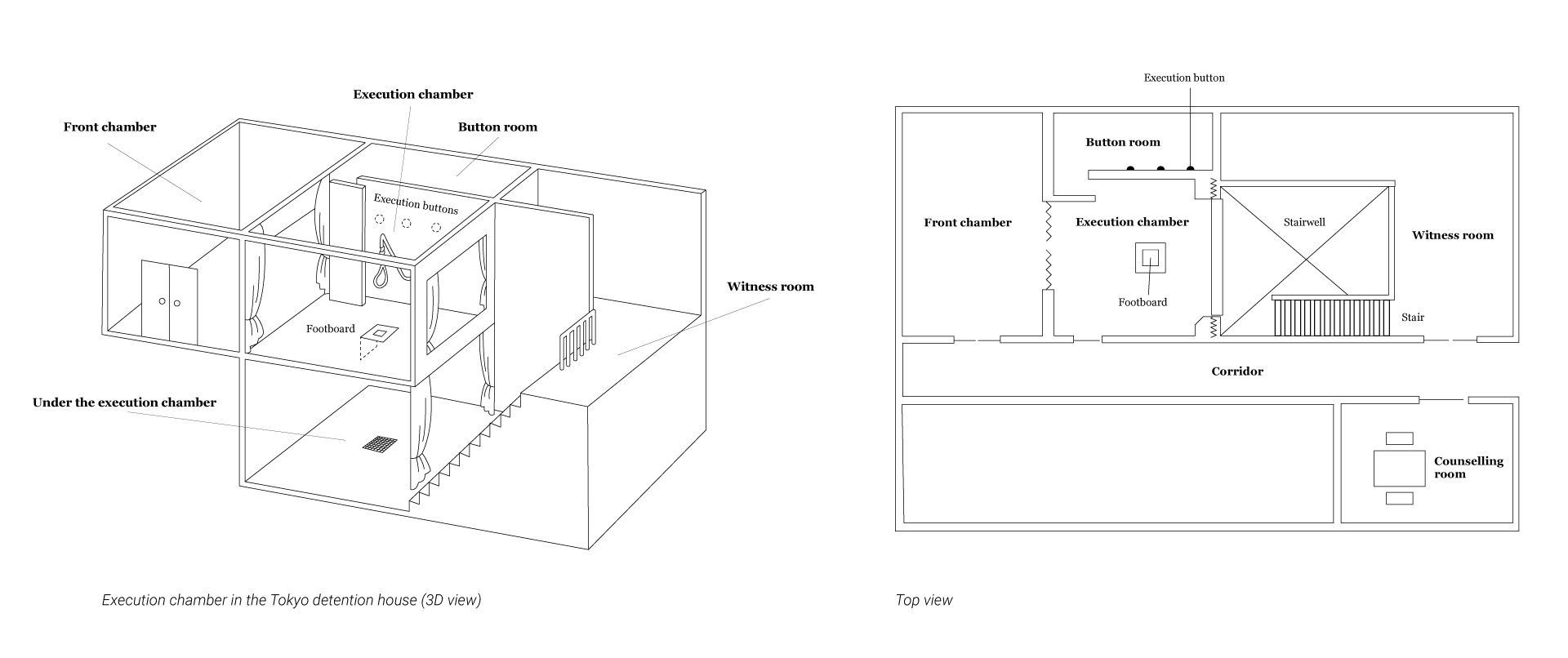

Invisible Hand is a kinetic sculpture that symbolizes the Japanese execution chamber used for the death penalty, a practice still in place and carried out more than 700 times since the Second World War. Executions are conducted by three executioners pressing separate buttons simultaneously to trigger the hanging. Only one button is connected and the others are dummies intended to lessen the executioners’ sense of guilt by obscuring who actually initiated the act. This deliberate anonymity reflects a modern anxiety toward committing to certain actions: in technologically advanced societies, people often evade responsibility by concealing the agency of an act through machines or instruments and by distancing themselves from its consequences. In the work, two witch brooms collide within a cloth-covered metal-framed structure, enacting an execution performed by an invisible hand, a magical intervention whose origin is unknown. Just as the death chamber is hidden behind a wall so the executioners cannot see the act or connect it with their own gesture, the installation’s white cloth isolates and alienates the space from the external human world.

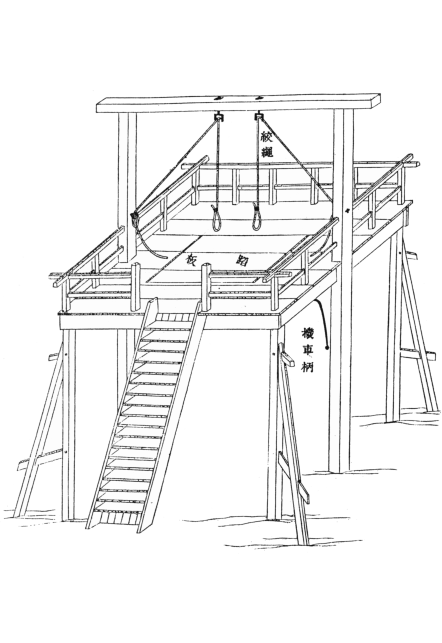

Although the exact origin of the three-button system is unclear, it echoes the blank cartridge method used in military executions during the First and Second World Wars in various countries. In those cases, one member of a firing squad was issued a blank cartridge to create the possibility that they did not kill the condemned and to soften the psychological burden. The idea is that uncertainty might comfort the executioner, at least in theory. In Japan, judicial hanging was officially devised in 1873 at the start of the Meiji era and formally adopted in 1880, during a period of radical political and social transformation as the country opened to the Western world. The new penal code designed the scaffold for hanging, and to this day only hanging is permitted for capital punishment. The law defines it as follows:

Grand Council of State Proclamation No. 65 of 1873

After WWII, Japan enacted a new constitution under the Allied occupation but did not abolish the death penalty, as the Allies themselves retained it. While many countries, especially in Europe, have abolished capital punishment, nearly 80% of the Japanese public continues to support its use (Based on the survey conducted between 2004 ~ 2019).

A condemned person never knows the exact date of their execution. On the day itself, they are taken from solitary confinement without warning, escorted to a chaplaincy room where sutras are read before a Buddha statue, then led into the execution chamber. They are handcuffed, their legs bound, blindfolded, and a rope placed around the neck. After being asked for any final words, a light signals the moment, the buttons are pressed, and the footboard opens. The executioners never see the act, as a wall separates the button room from the chamber. Five minutes after death is confirmed, the body is lowered, placed in a coffin, and removed. The anonymity of the act, built into the chamber’s architecture, serves multiple purposes. It may help those involved reconcile with their participation, reinforcing the perception that “the execution cannot be helped” since the doer is unidentifiable. It separates punishment from the appearance of interpersonal killing, allowing the law to claim that justice is carried out by an impersonal mechanism. In truth, the only physical force that completes the execution is gravity acting on the condemned’s own body weight, excluding any other direct human intervention. The executioners send their signal in the hope that they are not Connected. To carry out the death penalty in a state where heinous murder is punishable by death produces a paradoxical, almost schizophrenic twist.

In criminal law, two concepts measure culpability: actus reus (guilty act) and mens rea (guilty mind), established in Edward Coke’s Institute of the Laws of England in the 17th century. His principle actus non facit reum, nisi mens sit rea (“an act does not make a person guilty unless the mind is also guilty”) states that a crime requires both the act and the intent to occur together. Common sense distinguishes accidental acts from intentional ones: bumping into someone in a crowded train differs from deliberately colliding in an empty carriage. Responsibility arises only when intention is present, formed, and controllable. We do not resent a crying newborn, knowing the behavior is natural and beyond intent. Similarly, people with severe mental disorders may not be held culpable. This shows that recognizing guilt presupposes a boundary between human agency and uncontrollable natural forces and paradoxically, punishment assumes the criminal is a fully capable human being, just as one must believe in witchcraft to accuse a witch.

In today’s technologically advanced society, countless interfaces and communication tools transmit intentions across distances. Actions and consequences are increasingly separated and unobservable to their originators. One can harm systems or people remotely, through cyberattacks or unmanned aerial vehicles, without direct confrontation. Autonomous systems, such as artificial intelligence, classify and filter information without visible human oversight. In each case, only the outcome is apparent and the proactive human presence is concealed.

The Wealth of Nations (1776)

Adam Smith’s “invisible hand”, originally tied to market self-regulation, here extends to institutional and technological systems that obscure responsibility. Marx critiqued capitalism for alienating laborers from the products of their work, stripping them of intent and connection. The three-button execution method functions similarly, alienating executioners from the act of killing even as they initiate it. They act while hoping not to be directly connected. It also warns of the danger that modern states or powerful organizations might exploit machines and advanced technology as an invisible hand, avoiding accountability by erasing the subject from view. As processes become increasingly complex and interconnected, there is a growing risk of forgetting the human presence behind them, the only presence capable of taking responsibility.