Oh my ( )

2017

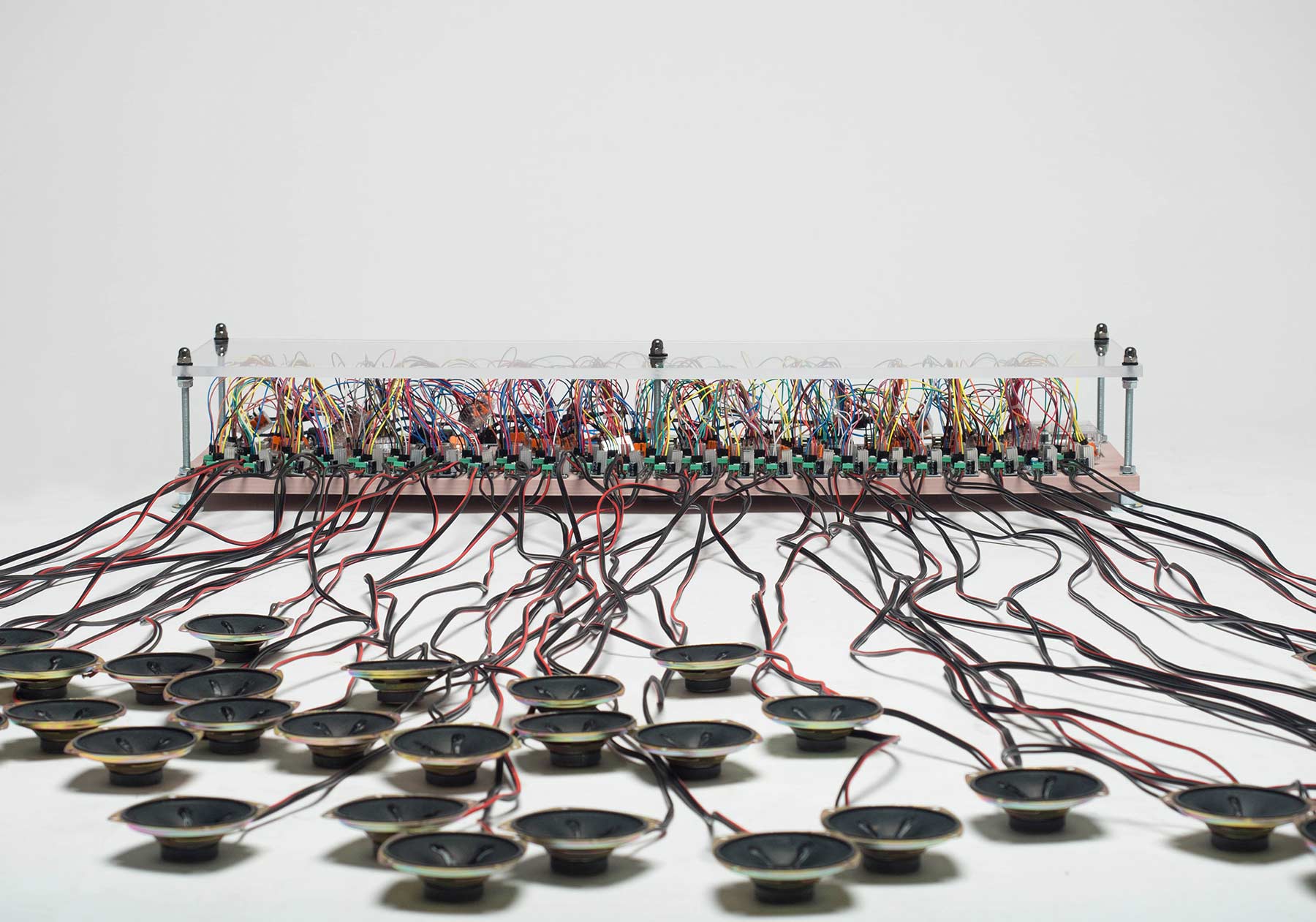

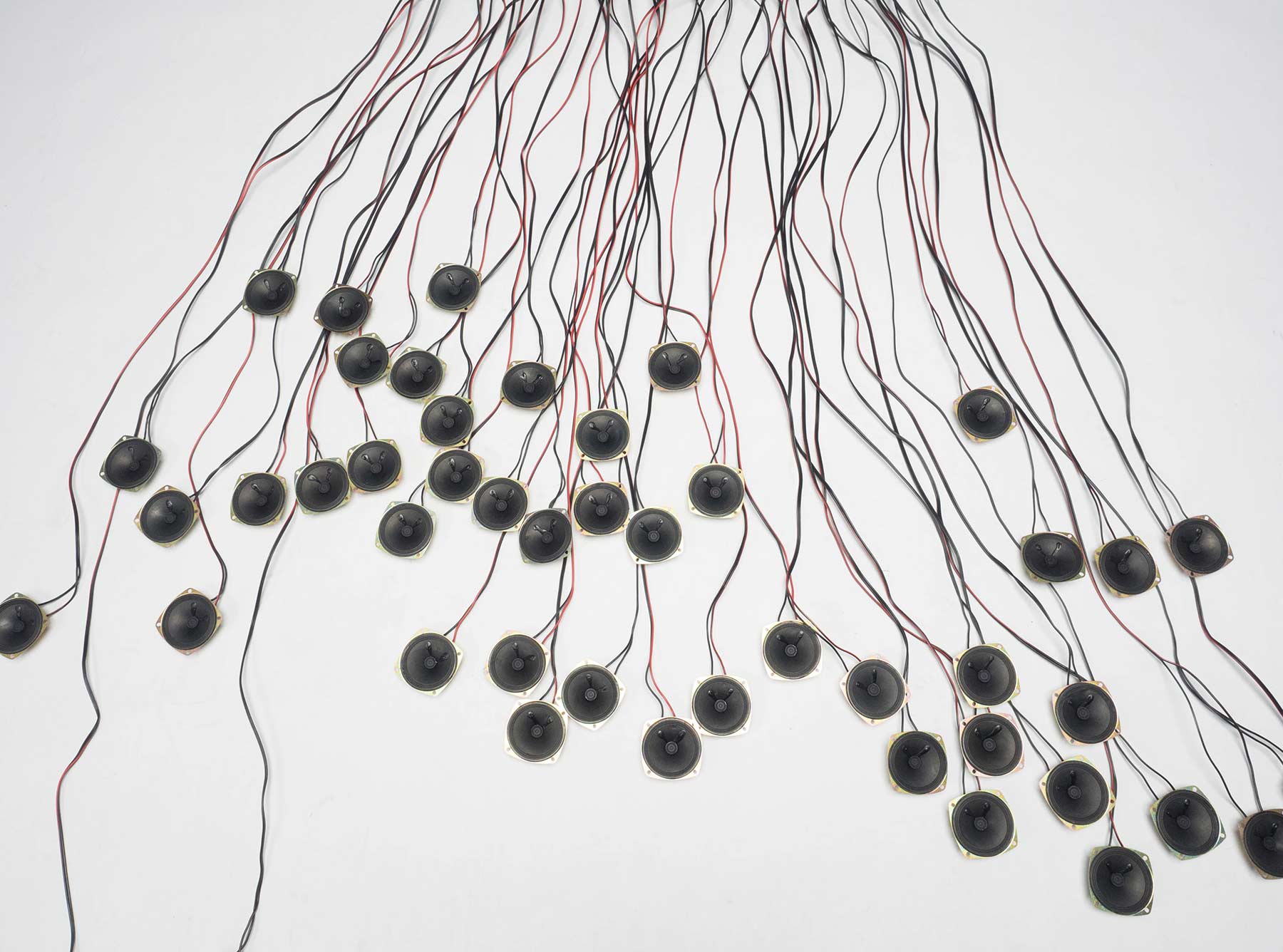

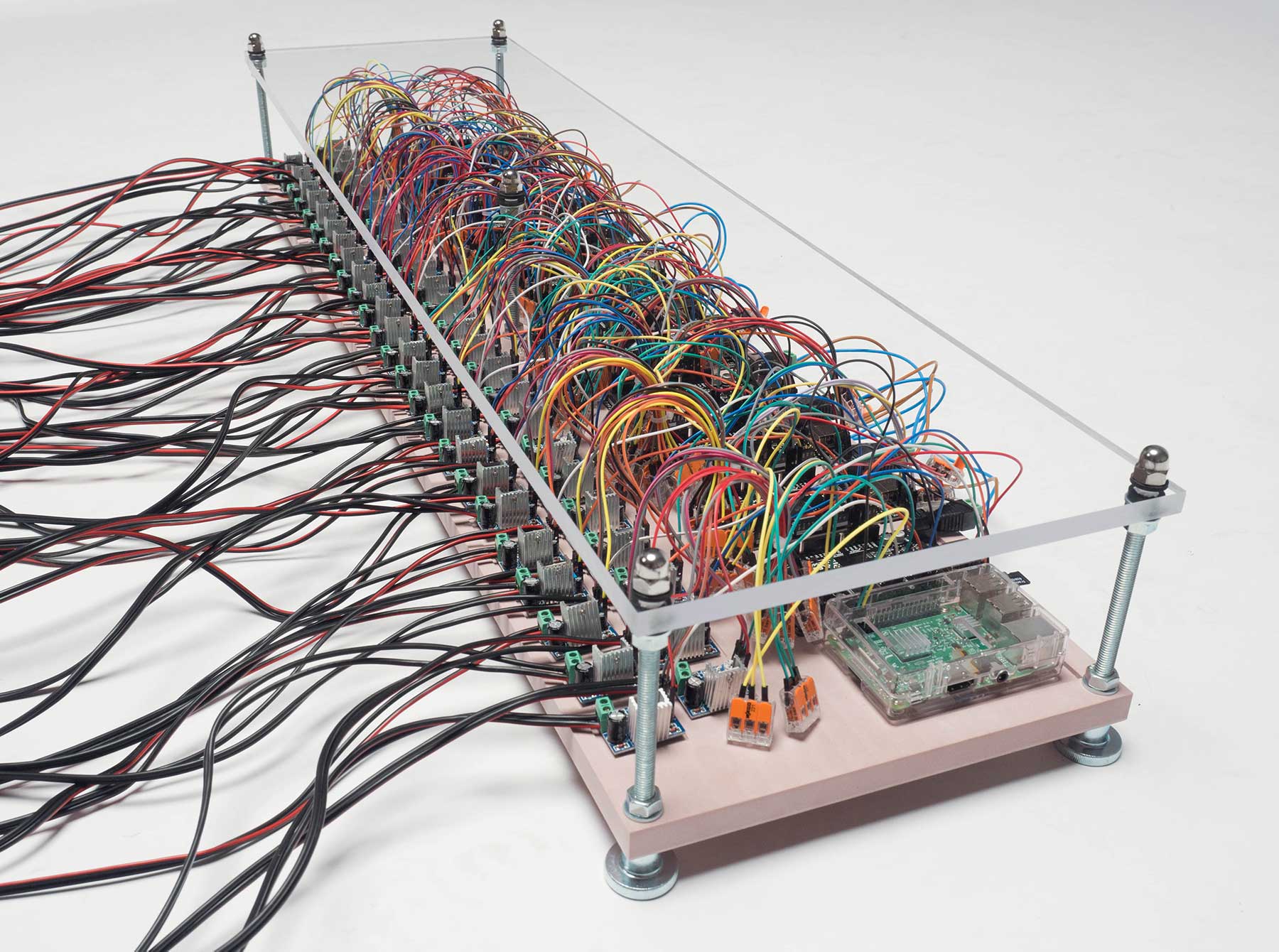

Installation

h160 × w300 × d150 cm

Oh my ( ) is an installation that calls out to God in 48 languages using data from Twitter. The machine monitors the Twitter timeline in real time, and when a tweet contains the word “God” (in any of the selected languages), speakers simultaneously play the phrase “Oh my [God in the tweeted language].” The list of accessed 48 languages is following.

The work references the cultural diversity and complexity embedded in the word “God,” shaped by religious contexts, historical interactions, and linguistic evolution. While a single term may seem natural within one cultural sphere, placing it alongside equivalents from other languages can reveal untranslatability, incommensurability, and tensions rather than harmony. Some languages have historically borrowed another culture’s word for God, though such exchanges are rare and often contentious. In monotheistic traditions, adopting a foreign term can appear paradoxical. Historical debates—such as the 17th-century “Term Question” in China over naming the Christian God, or similar disputes in 19th-century Korea—illustrate this challenge. Malta’s Catholic heritage, yet use of “Alla” due to its history of diverse rulers, and the contrast between Islam’s universal “Allah” and Christianity’s varied linguistic names, underscore political and strategic considerations in religious propagation. Despite the internet’s global reach, the number of languages most users encounter is limited, constrained by their own linguistic knowledge and the input capabilities of their devices. As Wittgenstein observed, “The limits of my language mean the limits of my world.” The installation also echoes the biblical Tower of Babel, where God confounded human speech as punishment. Here, the machine recreates the imagined aftermath: people, unable to understand each other, must have shouted to god against the severe punishment, "Oh my god" in their own tongues. The Twitter feed supplies a ceaseless stream of such invocations—some voices constant, others occasional—yet the listener can only perceive fragments amid the noise. While digital tools can analyze these calls, physically attending to every voice remains impossible. This raises a final question: does grasping such complexity bring us closer to democracy?